This story first appeared on The Hill and is also cross-posted on Ecosystem Marketplace.

story first appeared on The Hill and is also cross-posted on Ecosystem Marketplace.

March 29, 2019

The Green New Deal is a bold and controversial legislative resolution that seeks to simultaneously tackle both climate change and economic inequality. Since 2011, we’ve been empowering individuals and organizations to address their unavoidable carbon emissions through certified forestry projects which create income for rural communities in areas where earnings are typically less than $2/day.

So, we decided to write an op-ed to chime in on the public discussion of the Green New Deal in order to emphasize that its core concept is not new and, more importantly, to explain how what we do fits in. Our piece below was published by The Hill, one of Washington’s most respected and influential news outlets.

The Green New Deal was voted down in the Senate, but lives on in a changed conversation about climate policy, including among its critics. Many floated policy ideas they thought would work better or be more enactable. Others focused on what they think a deal should exclude. A big target of their fire has been carbon market mechanisms, especially carbon offsets. But offsets are a necessary part of any comprehensive approach to fighting climate change.

They have been around since the 1990s. Recently demand for offsets has risen fast, and could rise faster if federal or state climate legislation created compliance markets for them. Voluntary carbon markets are relatively small, and voluntary carbon offsets cut less than two tenths of a percent of annual global greenhouse gas emissions — but in a larger compliance market, where offsets help meet climate policy requirements, they could cut orders of magnitude more.

Some argued offsets should be off the table in a Green New Deal, claiming they are a license to pollute, don’t offer tangible emissions reduction, and can be exploitative toward developing countries.

The reality is complex — suffice to say the critics in many cases have been right. But they should not prevail, because excluding offsets won’t help the climate, whereas scaling up high-quality offsets will. We’ll make faster progress on emissions with them than without them.

Disney, Microsoft, Lyft and other major companies rely on offsets to cut net emissions. Etsy just became the first global e-commerce company to announce it will offset all its emissions from shipping. Cynics view offsetting corporate emissions as a cop-out. Offsets don’t stop GHG emissions at their source, so they don’t counteract giant companies’ emissions, they claim.

But there’s evidence that companies that use offsets aren’t trying to buy their way out of reducing emissions, they’re buying in. Studies show they consistently do more to reduce emissions than companies that don’t offset. There’s also evidence offsets really do counteract purchasers’ emissions. California got blowback for including forest offsets in its GHG reduction program, yet a Stanford study found they worked, cutting carbon emissions more than 25 million tons.

Globally, preserving and restoring forests could cut GHG more than eliminating all cars on earth. The UN climate process has stressed the need for carbon-negative strategies that effectively remove carbon from the atmosphere in order to draw emissions down faster. High-tech interventions like carbon capture and storage need decades and massive investment to scale up — but forests are nature’s original carbon-negative strategy, inexpensive, here and now. Offsets are the key to financing more of them.

Also, many types of GHG emissions — like air travel — can’t be stopped at the source. Plane exhaust is a big part of companies’ carbon footprints and there’s currently no way to fly without spewing it. Aviation emissions account for 5 percent of atmospheric warming, and are rising fast along with demand for air travel.

The Green New Deal FAQ mentioned scaling up high-speed rail so flying wasn’t necessary. When opponents seized on that, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez scrambled to deny she wanted to ground planes or outlaw private jets. But short of that, offsets are currently about the only way to mitigate growing aviation emissions.

That’s why Bernie Sanders just pledged to offset his air travel on the campaign trail, and why the International Civil Aviation Organization requires airlines to buy offsets.

A group of climate scientists wrote recently that unless the offsets support other GHG reduction that wouldn’t happen otherwise, offsets won’t compensate for rising aviation emissions — but the scientists also said offsets with “robust criteria” would work and would compensate for rising emissions.

Some offsets are more robust than others. To be effective, they must be “additional” (i.e., enable GHG reduction that wouldn’t have happened without them), quantifiable and verified by accredited third parties. Some offer other valuable benefits besides cutting emissions: reducing non-GHG pollution, alleviating poverty, or improving water and soil quality, biodiversity, food security and human health. Today, plenty of reputable offset providers meet these tests.

During the Green New Deal debate, some vehemently rejected carbon offsets as climate colonialism exploiting indigenous and rural communities. It’s true — and reprehensible — that some forest offset projects have threatened residents with relocation or disrupted livelihoods. Other projects that tout “net positive community impacts” like “well-being” or “capacity building” or “expanding knowledge” can be squishy and unimpressive when it comes to showing how much cash they put into local residents’ pockets.

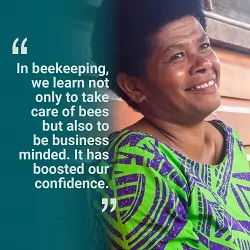

But these failings don’t typify the field. Offsets — when done right — genuinely enhance lives and livelihoods in rural communities. For example, Plan Vivo certifies offsets in parts of the world where incomes are under $2 a day. It requires that rural communities own their own offset projects and local residents receive at least 60 percent of all carbon revenues, so the money goes where it’s needed most.

A Plan Vivo forest offset project in Nicaragua generates direct payments to local farmers of about $300,000 a year. Another in Uganda, Trees for Global Benefits (full disclosure: my organization sells carbon offsets that fund it) has paid local households $2.5 million — the only cash income some of them have.

The money translates to improved human as well as forest health. Cash enables households to install running water and purification systems or qualify for loans to pay for medical care they wouldn’t otherwise get. TGB also protects medicinal tree species, including the African cherry Prunus africana, an active ingredient in prostate treatments.

Climate scientists and economists know that well designed, accountable forest offsets work. They also know that they have a perception problem. A group of them studied it, and found people see forest offsets more positively once they learn they’re cost-efficient at sequestering carbon. But their view of offsets doesn’t improve when shown how they also reliably cut emissions and confer other benefits like health outcomes.

Public perception should catch up to the reality. Our policy discourse is getting clearer about the imperative to connect climate action to social and economic justice. Our views on carbon offsets should, too.

They aren’t a panacea, or a substitute for stopping emissions at the source, and they’re not immune to abuses, but carbon offsets are still indispensable for cutting emissions and empowering people.

NOTE: This post has been updated from the original to clarify the medical use of Prunus africana.

Tim Whitley is the founder and CEO of Carbon Offsets to Alleviate Poverty (COTAP), a 501(c)3 public charity that sells offsets from certified forestry projects in least-developed regions which create transparent and accountable earnings for rural farming communities where income levels are less than $2 per day.

About The Hill

The Hill, which is known among those who influence policy as a “must read” in print and online, serves to connect the political players, define the issues, and influence the way Washington’s decision-makers view the debate. Since its launch in 1994, The Hill has been the newspaper for and about Congress, breaking stories from Capitol Hill, K Street and the White House. The Hill stands alone in signaling the important issues of the moment by delivering solid, non-partisan and objective reporting on the business of Washington, covering the inner-workings of Congress, as well as the nexus between politics and business.